I dropped out of college to go to work for the union. I had one semester to go. I was 21. It was a rash decision, but one at the time I felt incredibly sure of. What use is a philosophy degree? What the world needed more of was organizers.

I spent the first several months traveling the south alone. I hopped from hotel to hotel, knocked on doors to do surveys, dug through dumpsters to find employee lists, sat on the side of the road and recorded license plates of cars leaving a factory. I had little-to-no interaction with anyone from the union’s leadership or hierarchy. I received my marching orders from my hotel room phone or the front desk’s fax machine. I had no clue what I was doing.

I eventually ended up in the Hudson Valley of New York. For some reason they sent me there to help the business agent of a tiny local who had some interest from some workers at a pretty big agency that worked with developmentally disabled adults. Nobody in the union seemed to think much would come of it, but they promised him they’d send him help. He was pretty annoyed to find out it was a 21 year old apprentice with no experience.

I went around doing a door to door survey on labor conditions in the area, a standard ruse to see if there was any heat in the shop. Workers knew right away what I was up to. One after another said “thank god you’re here!” I wasn’t supposed to break my cover, but I was too green and too dumb to know any better. I organized a meeting of supporters I had met in my hotel. I called my contact in the union to let him know. He came up for the meeting. There were close to 50 people there. He flipped out. “Holy shit, this is a real campaign,” he said. “I need to call Sam.”

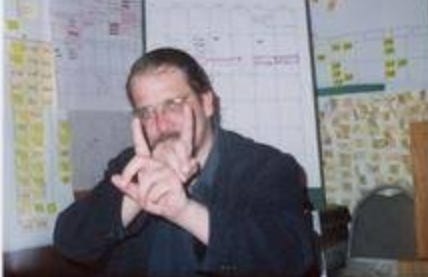

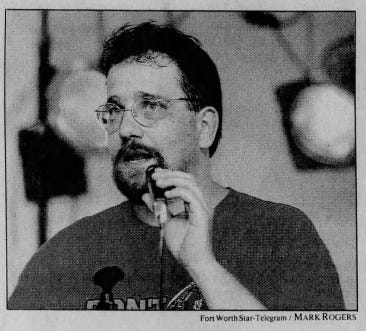

Within the week Sam showed up. He was about 10 years older than me, but he looked a lot older. He wore a big paddington bear coat, had a handlebar moustache, round glasses, and his hair was permanently mussed at the top. His eyes were always wide open. He fidgeted, spoke quickly and loudly, and alternated between being fiercely earnest and ridiculously silly. They told me he was a “mad genius,” and he certainly played the part well. I had always hoped that working in the labor movement I would meet people like this, and finally I had. I was eager to learn all I could from him.

Sam was an organizing director for the union who had lead some major campaigns. He had left for a while to live and work in London, where his legend only grew, and he had recently been recruited back to the union. This was going to be his first assignment back - running this campaign of 1,000 direct care workers in the Hudson Valley that I had messed up and brought out into the open half-cocked. I didn’t realize it then, but I was already starting off on the wrong foot with Sam and everyone else.

Sam brought in a team of organizers, some young and green like me, some with real experience, and we worked morning noon and night on that campaign. I slept in a murphy bed in the union office in the hotel, which is to say I never slept, since Sam was always in the office pacing the wall charts and reading organizers’ reports. It was a tough campaign, with the agency fighting tooth and nail with the support of the most expensive union busting law firm in the country. As the election drew nearer, I was overcome with panic. Winning that vote was the only thing that mattered to me on earth. I couldn’t think about anything else. I couldn’t entertain the idea of losing without doubling over with anxiety. I couldn’t think about those lawyers without dark and violent thoughts entering my mind. A lot of this is natural to this life and occupation, especially done in this fashion - dropped in from afar and staged in a hotel with no friends or family anywhere around and only the workers and their life stories and their struggles to gird you. But some of it was Sam’s influence, because this is also how he felt about this campaign. He was completely consumed with it. At times it seemed like he was going crazy. To him there was nothing more important than winning. Once he went to pick up a worker to drive her to vote, and on the way she refused to tell him how she was voting, so he drove her back home. Once he told the parents of a teenage worker who was on doctor ordered bedrest after a car accident that he would pay for an ambulette to drive that worker to the polls. Some of the organizers thought Sam had lost his mind. I was fully in his thrall. I felt like he knew how to win, and that was all I wanted, so I would do anything he told me to do in order to make that happen.

The vote count was, up to that point in my life, the most intense thing I had ever experienced. I thought I was going to throw up. They counted a thousand votes one by one. We won by 13 votes. When I looked over at Sam, his eyes were red, his cheeks were damp with tears. He was weeping. I imprinted on him. I would have followed him into oncoming traffic.

The day after the election Sam brought me into his hotel room and told me he was going to recommend that the union not hire me. I was shocked. I still remember what he said. “What, you think your work is above reproach?” He told me I was little use to the union. I didn’t speak Spanish. People didn’t like me. I was sloppy and disorganized. I wasn’t able to move people from undecided to supportive of the union. I wasn’t able to get people to do things they didnt’ want to do. All I was doing was finding people who were already pro-union and signing them up, and literally anyone can do that. Maybe I was smart, but “smart and a buck fifty will get you on the subway.” He agreed to extend my apprenticeship so I could stay behind and help the business agent with the first contract campaign there, and Sam moved on to whatever the union had in store for him next. When he left I hated him. But to believe he was wrong about me was to believe I was wrong about him. I wasn’t prepared to do that. So I committed myself even more than before to become the kind of organizer he could be impressed by.

It took a year to get the first contract, and Sam would pop in and out over that year to meet with me. By the end he offered me a job and brought me to Canada, where he had built a team of incredible organizers. Our charge was to organize essentially anything that moved. And that’s what we did. We ran up and down Ontario running elections at everything from plastics factories to domestic violence shelters, and we won virtually everything we ran. Sam cried at every single vote we won. Never when we lost. When we lost it was always, “get up and knock the dust off. Back to work tomorrow.” When we won, it was like a religious experience. It was overwhelming for Sam, and by extension overwhelming for all of the workers and organizers who worked with him, too. We took nothing for granted. We lived for those rare and fleeting moments where another world seemed briefly possible. In those moments, Sam always wept.

What I learned working with Sam was that he wasn’t a mad genius. After all, “smart and a buck fifty will get you on the subway.” He was smart, for sure. But what Sam had that made him a great organizer was that he was a true believer. Over the years I worked with a lot of “paycheck players,” pie cards who treated organizing like it was just a job. Sam wasn’t a paycheck player. In a very real way, Sam had committed his whole life to the union movement. He believed in the cause of organized labor, in the power of class solidarity, and he believed that workers - with everything aligned against them and nothing but truth on their side - could win. And he lived on the road for decades in service of this belief, working around the clock, day after day, taking little time off to do anything else.

I grew close to Sam during this time. I met his family, visited their home in tony Long Island and played tennis with his young niece. I shared countless meals, movies, and ball games with him. He gave me books to read. He told me war stories. We drag raced our rental cars on deserted country roads. We detonated countless fireworks. He got me out of jail after a wild globalization protest. We chased scabs from picket lines. We partied with workers we met from countries I had never heard of. He introduced me to the woman who would later be my wife. We cooked up crazy schemes and pulled off shit I wouldn’t dare write about here, but would gladly tell you about over drinks. He was my boss, but at that time in my life he may have been my best friend. Then one day he got a job at the AFL-CIO in D.C. and he left. He didn’t tell me or anyone else on our team about it. He basically gave us the Irish goodbye. And after he left we drifted apart. He came to my wedding, emailed me the occasional link to a funny video, or called me when my dad died. But we grew to become virtual strangers to one another.

Years later Sam would tell me that these years that our paths crossed and I worked for him were perhaps the worst years of his life. I won’t get into it. He wanted to apologize for things he did. But I was too young and naive and green to recognize any of it. To me, Sam was The Most Interesting Man in the World. He was always the center of gravity in any room he was in. Nearly everything he said carried profundity, and what didn’t was usually the funniest thing you had ever heard. He was the first real mentor of my young life. He had a profound and positive effect on me and the person I would become. If that was Sam at his worse, I am forever jealous of everyone who got to know him at his best, in all of the years that came after that.

Sam found strength later in life through faith. When my father was dying he reached out to offer support. He told me “You have to have some faith in times like these, bro.” I’m not sure I had much faith at that point in my life. Things were definitely falling apart for me. I ended up leaving the labor movement shortly after. I know that one of the things that fueled me back in those early years when I worked for Sam was faith - not only in the movement, but in him. I had a tremendous amount of faith in his ability to figure out a solution to nearly any problem, to have the necessary courage to meet whatever the moment threw at us, and to have my back when I needed it. They say that faith the size of a mustard seed can move mountains. We moved a lot of mountains in those days, dark as they may have been for Sam.

Sam unexpectedly died this week. He left behind a beloved wife and a son that he adored. His son just turned 14. Sam’s own father died at the age of 48, when Sam was very young. His father’s name was Melvin, and Sam’s given name was Melvin as well. I learned this fact late one night when Sam and I and a group of organizers were at karaoke and Sam sang the Johnny Cash song “Boy Named Sue” but changed the lyrics from “Sue” to “Melvin.”

The song, written for Cash by the poet Shel Silverstein, is about a man whose father left him at a young age, and how he tracks his father down to kill him as revenge for giving him the name Sue. He eventually finds him and a fight ensues:

Well, I tell you, I've fought tougher men

But I really can't remember when

He kicked like a mule and he bit like a crocodile

Well, I heard him laugh and then I heard him cuss

And he reached for his gun but I pulled mine first

He stood there lookin' at me and I saw him smile

And he said, "Son, this world is rough

And if a man's gonna make it, he's gotta be tough

I knew I wouldn't be there to help you along

So I give you that name, and I said goodbye

And I knew you'd have to get tough or die

It's that name that helped to make you strong"

He said, "Now you just fought one heck of a fight

And I know you hate me, and you got the right to kill me now

And I wouldn't blame you if you do

But you ought to thank me, before I die

For the gravel in ya gut and the spit in ya eye

'Cause I'm the son of a bitch that named you Sue"

What could I do?

Well, I got all choked up and I threw down my gun

I called him my pa, and he called me his son

Come away with a different point of view

And I think about him, now and then

Every time I try and every time I win

Well, if I ever have a boy, I'll name him

Frank or George or Bill or Tom, anything but Sue

I don't want him go around, man call him Sue all his life

That's a horrible thing to do to a boy trying to get a hold in the world

Named a boy a Sue

When Sam finished singing his eyes were red, his cheeks were damp with tears. He was weeping.

****

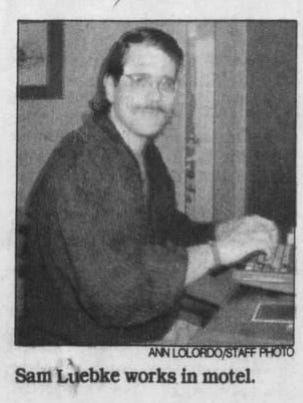

The following profile of Sam appeared in the Baltimore Sun in 1993, early in his career and well before I met him. It’s a fascinating glimpse into Sam’s life, ideals, and thoughts of his own future. It’s also a very accurate portrayal of the life that road organizers lived, even a decade later, and how all-consuming that work could be.

On the road for the union: Organizer wages uphill fight

By Ann Lolordo, Baltimore Sun

ST. MARTINVILLE, La. — Days after a winter storm ushered in the New Year, Sam Luebke is back in this sleepy bayou town, driving down one-lane roads and rain-slick highways, through swamps and along sugar cane fields, past commercial strips and trailer homes, to knock on doors.

He is back visiting the shirt-hemmers and “incheckers,” the sleeve-setters and neck-binders, the garment workers he is trying to unionize. He’s back at the Comfort Inn in Lafayette, in a room down the hall from the one he lived in for 69 consecutive days before Christmas.

And he’s still driving the dusty black Ford Taurus with most of what he owns — three crates of books (Hemingway, McPhee, Orwell, Nietzsche, to name a few), plastic garbage bags (to pack clothes in a hurry), New Balance sneakers (“the only running shoes made in he United States”) Federal Express envelopes, a computer, fishing equipment — crammed into the back seat and trunk.

If it’s Wednesday, this must be St. Martin’s Parish. And Sam Luebke, an organizer for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers, is working the Cajun countryside of this right- to-work state, where unions are about as welcome as cane borers and “No Union” signs outnumber American flags on a small town’s Main Street.

Throughout this country, unions have watched their membership decline, while the number of employed people has grown. A decade ago, 20.1 percent of hourly workers held union cards. That is down to 16.1 percent, and unions have begun to realize the need to shore up membership and organize new sectors of the economy.

The new recruits are often young, college-educated organizers such as Sam Luebke. They follow a path worn well by organizing heroes from Joe Hill to Walter Reuther, a tradition that flourished in the factories of the 1930s. They are taught by organizers who honed their skills on shop floors as well as in the anti-war and civil rights movements.

Their challenge is to overcome the blows dealt the labor movement in the 1980s by Washington policy-makers, anti-union attitudes and the shift from an industrial to a service economy.

Mr. Luebke is a believer. At 26, he has “never seen a factory where folks don’t need a union.”

A former paralegal with a high-priced Manhattan law firm, he left Wall Street for “no fixed address.” He’s a chain-smoking, mustachioed New Yorker paying union dues instead of club membership fees, the only son of teachers whose family roots span rural Wisconsin and the Chicago stockyards.

This January week, his targets are two Fruit of the Loom garment factories with 5,000 workers, the biggest shop in which Mr. Luebke’s southwest region has waged a campaign. The last union organizers who handed out leaflets at these plants got arrested.

“These are little towns, and believe me the police are not all card-carrying members of the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union],” Mr. Luebke says.

‘The same old company’

Today, the “black bull” (as the leased Taurus has been dubbed) is headed for the homes of mill workers, women whose hands grow calloused and knobby from sewing hundreds of T-shirt hems a day.

He pulls into a dirt driveway on a darkened street in Breaux Bridge, a town of 6,515 deep in bayou country. Mr. Luebke climbs the concrete steps of a mobile home and knocks. Two young boys fling open the door. “It’s Sam! It’s Sam!” they shout.

Charlotte Lewis comes to the door, her head still covered with a hair net, the kind mill women wear to keep lint out. “Hey,” she says, inviting Mr. Luebke in and returning to the stove, where a pot of red beans and sausage simmers.

For 17 years, Charlotte Lewis has worked at Martin Mills in St. Martinville, a historic town of 7,100 that is the parish seat and the site of the Evangeline Oak memorialized by Longfellow.

She sews boy’s briefs, 48 pairs of underwear per bundle, 44 bundles a shift, about $70 a day.

“They think you-all left,” Ms. Lewis says to the union organizer in her Cajun lilt, “and things been happening. They want to know where you-all at.”

Mr. Luebke and the other union workers went home for the holidays. “What’s been happening?” he asks.

Ms. Lewis opens the stove door with a hand towel, pulls out a hot tin of corn bread and pokes its spongy top. “They never

promote nobody. But now they be taking people’s names down who’ve been there awhile,” she says, referring to the promotion prospects. “That’s to settle people down, to try and make the people feel good, that like Martin Mills is changing.”

“People are going to see it’s the same old company,” Mr. Lewis says.

“Every time we get a raise, there’s more we have to do. They just keep pushing you.

“Every year it get worse. . . .

“They brought me in the office already because of the union,” says the 36-year-old mother of three. “[The plant manager] dared me to open my mouth. He told me I was going to lose my job if I ever talk about it. But I always get my word across.”

This union fight isn’t about money, she and others say. People want better working conditions: a vacation other than the two weeks the plant shuts down around the Fourth of July and Christmas, a relaxation in production quotas if a sewing machine breaks down, paid sick leave to accompany health and retirement benefits (a worker who misses 90 hours a year can be fired, regardless of illness), and even application of rules to blacks and whites.

Despite the union’s recent presence here, the organizers have been able to see only about a third of the work force at the two plants. The union needs at least 30 percent of the workers to sign union cards before an election can be held.

“They’re so scared, think they’re going to lose their job even if they look at a card,” Ms. Lewis says of her co-workers.

‘They want a change’

For Sam Luebke, people such as Charlotte Lewis are “gold” — smart, forthright, not afraid to say what they think, tireless, believers.

“People here want a union. They want a change, but they are so terrified . . . of the managers and challenging the authority figures in this area, so we are making pretty slow headway,” says Mr. Luebke, who favors flannel shirts, cotton sweaters, cowboy boots and twill pants.

“Before I got into organizing, I thought people didn’t work in factories anymore,” he says.

As a college student studying in Brazil, Melvin William Luebke Jr. saw organizers of the most basic kind — church-backed activists working to gain land rights for the poor. But it was a weekend in southwestern Virginia in the fall of 1989 that became the seminal event in his career.

At a friend’s urging, he drove to a support rally for striking coal miners. Thousands of miners, dressed in camouflage, converged the mine entrance and held a vigil for three days. No one was arrested.

“That just kind of got me hooked,” he says. “After that, there was no choice. It was really in my blood. . . . I would’ve done anything to work for a union.”

By mid-January 1990, after having helped organized labor support David N. Dinkins’ campaign for mayor of New York, Mr. Luebke was off to North Carolina as a $350-a-week organizer for the textile workers.

Finding the people who count

When you’re one of four organizers in an area about the size of Peru, you live in a hotel close to the interstate with a refrigerator and microwave in your room and desk clerks who welcome you back. You lease a midsize sedan with air bags and a tape deck on which to play your cache of Delta blues and labor movement balladeers. If you’re Sam Luebke, when you pull into a town you find the newsstand with the most out-of-town papers, a good dentist (“I have terrible teeth”) and a deli that sells pastrami on rye.

And, whether you’re organizing plastics workers or food processors, you find the employees who count: the seamstress who keeps the birthday lists, the laster who knows where to find the prime fishing holes, the machinist who can make a carburetor purr.

“My job is to tap into the informal social networks and turn the natural leaders into union leaders,” says Mr. Luebke, who now earns about $27,000 a year. “You can write the best leaflets in the world, but if you can’t identify who’s important, you’re not going to be able to get anything off the ground.”

Mr. Luebke works more than 40 hours a week to give workers a shot at an eight-hour day. There have been months without a day off (although his union contract guarantees him every other weekend at home), too many factory workers whose names he can’t remember, too much HBO in place of a nonexistent social life, and four inches on his waist from roast beef dinners at a Pennsylvania truck stop.

Only once has he been threatened. Anti-union workers from a bicycle factory in Pennsylvania arrived unexpectedly at a meeting Mr. Luebke held and told him, “If you don’t get out of town, we’re going to bust your legs.”

Mr. Luebke lost that campaign, but only after workers on both sides of the issue agreed to attend a debate he sponsored on pros and cons of a union.

Today, companies don’t need to resort to violent tactics, he says. They hire big law firms that devise strategies for inundating the workers daily with anti-union messages, mandatory employee meetings and video presentations.

“The company can spread their message to every single person in the plant every single day, while we are reduced to visiting people in their houses or having meetings that people are scared to go to,” Mr. Luebke says.

Unlike manufacturers that have moved plants overseas, Fruit of the Loom has opened new plants in job-starved towns, bringing its work force to 32,000.

Company executives contend that they have never threatened to close a plant in the face of a union contest, but they acknowledge that higher wages won by unions would hurt their ability to compete.

All but one of the company’s 24 U.S. plants are nonunion.

“We don’t feel we need an outside party to solve any problems we might have. We feel we can solve them within the family, so to speak,” says M. Jack Moore, president of Fruit of the Loom’s Kentucky-based operating company.

“The Bible says, ‘Treat other people like you’d like them to treat you.’ That’s the philosophy of this company.”

A job for idealists

On a drab, overcast day, Sam Luebke is driving to Jeanerette (population 6,200, where work can be found in a sugar mill or a sewing plant) to interview a woman who was fired from her job two days after she held a union meeting in her front yard. The union may be able to win her job back if it can prove that the company treated her differently from other employees and that her supervisors knew she supported the union.

In Jeanerette, most women who don’t go to college or into the military work at a plant. A sugar mill rises in the middle of town like a rusted hulk made of tin cans. Billowing white smoke from the mill rolls across the road, and the air smells sickly sweet. Mr. Luebke turns down Cypremort Street, a shabby lane of weathered, tin-roofed cottages and mobile homes.

“Basically, the reason I do this is people in the United States have a decision to make . . . a choice, of treating the people that actually work for a living in this country like animals or machines and gradually having us become more like Brazil or Mexico or recognizing that people have basic rights that all people deserve, like the right to be treated with dignity, the right to health care, the right to work in a safe environment,” he says.

In three years, in campaigns from Lawrence, Kan., to Denton, Md., Sam Luebke has lost all but one battle, at a Missouri shoe factory. But in this business, an organizer’s success can depend as much on which plants his union has targeted as on strategy, resources and leadership.

Organizing has become such an arduous task “that you can only get idealized 26-year-olds to do it because of the pain and the sorrow and the enormous hardships involved,” says Chicago lawyer Tom Geoghegan, author of “Which Side Are You On,” a history of the modern U.S. labor movement.

“We don’t have laws in this country to allow people to freely and fairly join a union [without the risk of] being fired,” he says. “The power is so overwhelming on the side of the employer.”

Someday, Mr. Luebke says as he is driving back to Lafayette and a catfish dinner, he would like “to get off the road,” get married and have a family.

“I don’t want to live [this way] my whole life,” he says.

But meanwhile, Sam Luebke is mentally plotting the route to his next stop. He’s gotten word: In Arkansas, another campaign awaits.